Design Patterns for Container Based Distributed Systems

#design patterns #clean code #dockerThis article is inspired from paper titled with the same name published by Brendan Burns and David Oppenheimer

Containers now a days are becoming more and more analogous to objects in object-oriented programming. Like objects, containers should be small and should do one and only one thing. That’s just another way of saying Single Responsibility Principle. We are seeing a similar trend from the late 1980s and early 1990s when object-oriented programming revolutionized software development. Containers have become the “object” in the distributed systems. Like objects, they expose an API. They have erected a wall so that other containers can’t interfere. Like design patterns for objects, we have design patterns for containers too. And now I think we are just waiting for another Gang of Four.

In this article we will see few single node, multi-container application patterns. Meaning, these patterns are applicable to a single host machine (or kpod for Kubernetes or task group for Nomad).

Side Car Pattern

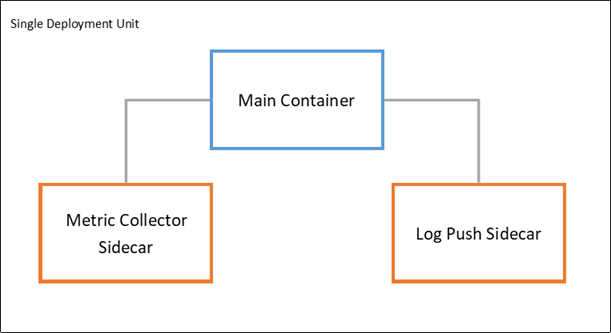

Sidecar extends/enhances the main container.

Well, that’s the gist of it. Imagine anything add-on that you want to run with your main container. If you are familiar with the decorator pattern (in Object-Oriented world), I would say this is that.

The standard use cases explained everywhere for this pattern is log saver — your application writes logs to the disk and a side-car container pushes these logs to some other service. Although this can be incorporated in the same container but “separation of concerns”, “single responsibility” and all these fancy terms ask us not to. I would try to come up with some hypothetical use cases of Sidecar pattern.

Use Cases

You have a monitoring system where you want to push metric from your main container (could be logs, could be few numbers, could be anything else).

You need to periodically pull data from another service or update a local cache based on that.

You need to send emails to your users, and you already have this is a container built. Now that container can be reused.

Hazelcast supports this pattern wherein instead of having a separate cluster, you could just run sidecars with your main container and groups of these container would form a cluster.

Figure 1: Example of sidecar pattern with a main container and two sidecars to collect metrics and push logs in a single deployment unit

Ambassador Pattern

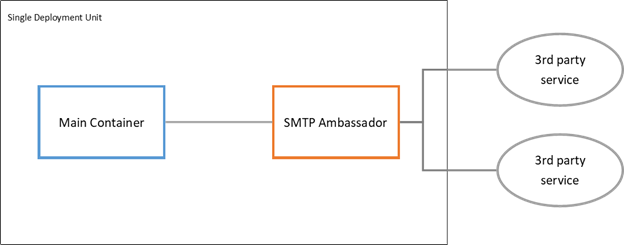

Acts as a proxy to another container world

Ambassadors are possible because containers in a pod share the same network. So, you can simply connect via localhost. Now, when you are developing something, you don’t have to worry about connecting to clusters and all, you can just connect to a service on localhost, and you are done. The ambassador handles connecting to the cluster or some third-party service. First it becomes easy to code. Second, it’s easy to test since you just need this ambassador and not the actual service.

Use Cases

Connecting to a SMTP service like SendGrid when you have a simplified interface in localhost but all the talking is taken care by the ambassador.

Your third party service needs security. You can offload the interaction in ambassador container and main container can simply communicate to the ambassador.

Ambassador can also take care of retries in case communicating with an unreliable service.

Although you would have a central place to manage your API, but ambassador can be used to act as a circuit breaker when you want other services connecting to your container.

Figure 2: Example of Ambassador container that interacts with a 3rd party SMTP service. It manages all interaction including security, retires in case of failure

Adapter Pattern

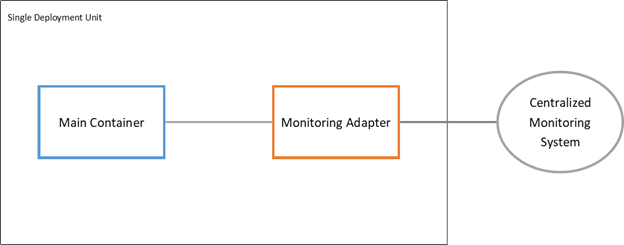

Just like the adapter pattern of object-oriented world

An adapter like the adapter design pattern presents the main container to the outside world with a predefined interface. It adapts to a requirement that our container is supposed to adhere.

For example, consider that you have a monitoring service that expects all the containers to expose isHealthy and getHealthStats endpoints on a certain port. Now it’s possible that few containers don’t comply with this requirement or for few containers this information is not readily available or you need to query 3 different endpoints to get this. An adapter comes to the rescue. The main container can run without any changes. We deploy an adapter that performs all these tasks and exposes the required endpoints.

As with the adapter of object-oriented world, the use cases are many. I’ll try to add some hypothetical applications.

Use Cases

You have a work execution framework with different kind of work units that must comply with a single interface.

Your main container provides endpoints over web-socket, but you need them over HTTPS.

Your container has a single API format, but different services expect it to have it in their format. So, you deploy multiple adapters to adhere to those requirements.

Figure 3: Example of Adapter pattern. The Monitoring Adapter exposes endpoints to track the health of the main container adhering to the unified interface required by the centralized monitoring system

Summary

We are seeing a similar trend that we saw with objects in object oriented paradigm. Containers have become objects and few of the design patterns are getting reused. We saw three design patterns:

- Sidecard, Decorator. Deploy additional functionality with the main container, augment it’s behavior.

- Ambassador, Gateway. Offload communication to another container

- Adapter, Adapter. Adhere to requirements/standards from outside our control

References

- Burns, Brendan and Oppenheimer, David. Design patterns for container-based distributed systems

- Ambassador Pattern, Microsoft Cloud Design Patterns

- Hazelcast Sidecar Container Pattern